“When an old man dies, a library burns.”

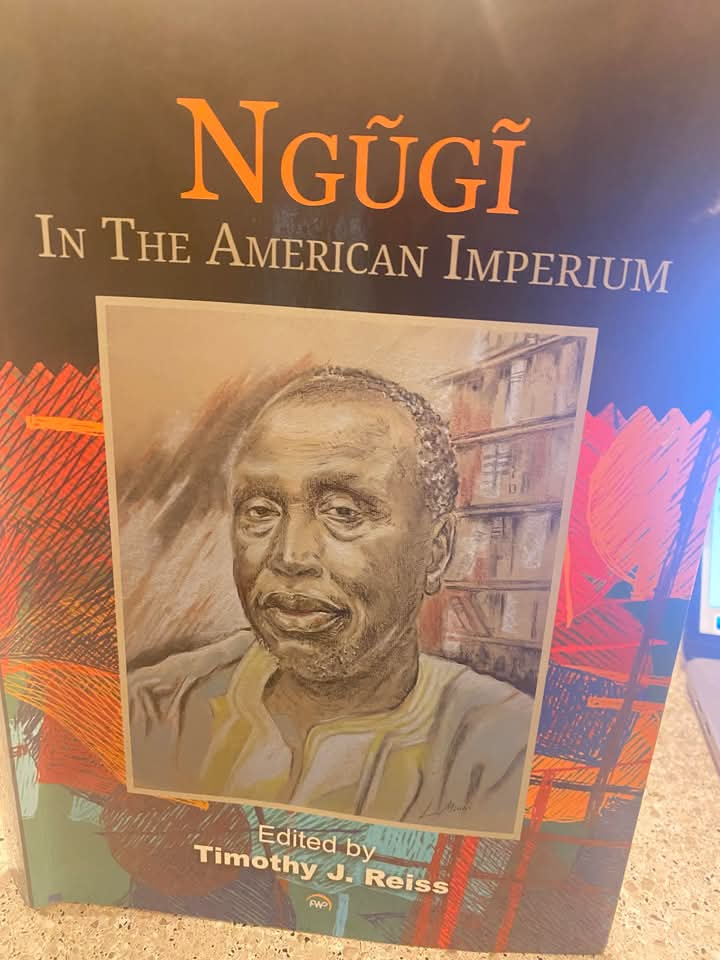

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the Kenyan novelist, playwright, and intellectual powerhouse who redefined African literature and waged a lifelong war against linguistic imperialism, has died at the age of 87.

His family confirmed that Ngũgĩ passed away peacefully on Tuesday morning, surrounded by loved ones. The cause of death has not been made public, but tributes are pouring in across the world, from literary circles in Nairobi to academic halls in New York.

For nearly six decades, Ngũgĩ remained a moral compass for post-colonial Africa, wielding his pen like a sword to expose the lingering wounds of colonialism, authoritarianism, and cultural erasure.

“His words were fire,” said Mukoma wa Ngũgĩ, his son and fellow writer. “They did not just speak truth, they made truth tremble.”

From Kamiriithu to the World

Born in 1938 in Kamiriithu village, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, then James Ngugi, was shaped by the turbulence of colonial Kenya. The Mau Mau uprising tore through his family: his brother joined the resistance; his mother was tortured; the family land was seized. These early scars etched themselves into his fiction, infusing his work with urgency, memory, and resistance.

After studying at Makerere University, where his path crossed with Nigeria’s Chinua Achebe, Ngũgĩ published Weep Not, Child (1964), the first English-language novel by an East African. It was followed by The River Between (1965), A Grain of Wheat (1967), and Petals of Blood (1977), cementing his status as a post-colonial literary titan.

But it was Decolonising the Mind (1986), his groundbreaking manifesto, that redefined his legacy. Ngũgĩ denounced the use of colonial languages by African writers, calling it “the most subtle form of enslavement.” He urged a radical return to African languages, sparking decades of fierce debate and admiration.

“To write in Kikuyu was to say: I am. To write in English was to say: I was told,” Ngũgĩ famously said.

Arrest, Exile, and Literary Rebirth

In 1977, Ngũgĩ was arrested without trial for co-writing Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), a biting critique of inequality performed by villagers in his hometown. While imprisoned, he wrote Devil on the Cross in Kikuyu, on prison-issued toilet paper. It became a symbol of resilience and literary defiance.

After his release, a near-fatal assassination attempt forced Ngũgĩ into exile in the 1980s. From London to California, he continued to write and teach, publishing novels like Matigari (1987) and Wizard of the Crow (2006), a satirical epic hailed as a modern African classic.

His works, now translated into dozens of languages, appear on syllabi from Nairobi to Harvard. Yet Ngũgĩ remained rooted in the soil of African orature, philosophy, and peasant wisdom.

“You can’t milk a lion and call it a cow,” he once quipped, challenging the West’s appropriation of African narratives.

A Legacy Written in Stone—and Language

Ngũgĩ’s insistence on language as the soul of identity reshaped African literature, even as it estranged him from early mentors like Achebe. He believed that true liberation could not come through borrowed tongues.

Despite personal trials, detention, exile, a brutal attack during a 2004 return to Kenya, and health setbacks—Ngũgĩ never softened. His final years were spent mentoring young writers, championing African languages, and reflecting on his unfinished mission.

“The most dangerous creation of any society is the man who has nothing to lose,” James Baldwin once warned. Ngũgĩ, by contrast, had everything to gain—for Africa.

He is survived by his wife, Njeeri, and several children, including Mukoma wa Ngũgĩ. He leaves behind a literary canon unmatched in courage, scope, and spirit.

In a world increasingly seduced by noise, Ngũgĩ’s voice rang with clarity. He taught us that a story, told in one’s mother tongue, can outlive bullets, prisons, and time itself.

The pen, in Ngũgĩ’s hand, was never just mightier than the sword, it was the sword.